By Umair Ahmed, B.B.A., LL.B. (Hons)

Introduction

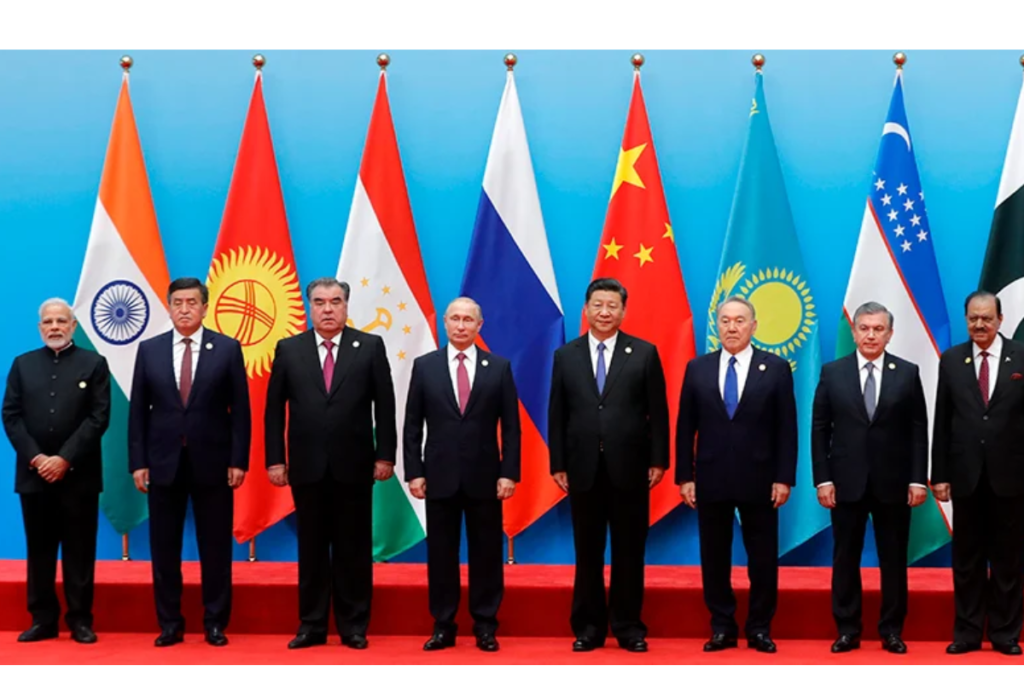

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is a pivotal regional body comprised of member states including China, India, Pakistan, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The organization’s global relevance is anchored in its immense energy resources; member states collectively control approximately 25% of the world’s oil reserves, over 50% of global gas reserves, and significant portions of coal and uranium. While the SCO’s original common ground was established to address regional threats of terrorism, separatism, and extremism, its focus has since evolved to prominently include energy security and economic development. This shift is facilitated by platforms like the SCO Energy Club, which brings together energy producers, consumers, and transit nations to foster cooperation. As these nations engage in unprecedented cross-border energy and infrastructure collaborations, they also face a shared internal challenge that threatens this progress: overwhelming judicial backlogs that undermine economic development and public confidence in legal institutions

EMERGING CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS IN DISPUTE RESOLUTION AMONG SCO MEMBERS

Introduction:

The member states of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) share a common challenge that threatens economic development and undermines public confidence in legal institutions: overwhelming judicial backlogs. This systemic issue cuts across jurisdictions regardless of their legal traditions or economic development status:

- In India, the Supreme Court faces a backlog of 82,000 cases[1], High Courts over 6.2 million cases[2], and lower courts around 46 million pending matters[3]. Nearly 5 million cases remain unresolved despite increasing attention from successive Chief Justices.[4]

- Sri Lanka’s judicial system struggles under the weight of over 1.1 million pending cases, as reported by the Ministerial Consultative Committee on Justice and National Integration.[5]

- Pakistan’s judiciary faces similar challenges, with recent reports indicating over 2.1 million cases pending across all court levels, with the Supreme Court alone handling a backlog exceeding 54,000 cases.[6]

- Other countries like Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan are implementing judicial reforms to improve efficiency, such as digital case management systems and institutional restructuring, even as they face challenges like growing caseloads and resource limitations.[7]

This judicial congestion creates a critical impediment precisely when SCO member states are pursuing unprecedented cross-border energy and infrastructure collaborations. As these nations collectively control 25% of global oil reserves and over 50% of gas reserves, effective dispute resolution mechanisms are essential for economic cooperation.[8]

The complexity of cross-border energy disputes—involving state actors, technical specifications, and massive capital investments—demands specialized arbitration frameworks beyond traditional litigation. Artificial intelligence offers promising tools to analyze complex contracts, predict potential conflicts, and streamline processes that currently consume valuable resources.

This paper examines how specialized arbitration mechanisms, enhanced by artificial intelligence and aligned with sustainable development goals, can transform dispute resolution from a bottleneck to a catalyst for regional integration across the SCO region.

Strategic Context of SCO Energy Cooperation

The SCO member states collectively control approximately 25% of the world’s oil reserves, over 50% of global gas reserves, 35% of coal reserves, and roughly 50% of known uranium reserves. This resource wealth positions the SCO as a potential powerhouse in global energy governance. Central Asia has emerged as an alternative energy source for growing economies like China and India, whose sustained economic growth depends on uninterrupted access to energy resources.

The SCO Energy Club, established in 2013 as a non-governmental consultative mechanism, has evolved beyond its original focus on addressing terrorism, separatism, and extremism to encompass energy security and economic development. [9]This platform brings together energy producers, consumers, and transit nations to address shared concerns, with participation extending beyond SCO members to include Mongolia, Belarus, Iran, Afghanistan, and Sri Lanka – all crucial players in energy transportation to major markets including China, Japan, Europe, Korea, and India.

Emerging Challenges in Dispute Resolution and Regional Cooperation

Legal Fragmentation and Cross-Jurisdictional Challenges

Competing Dispute Resolution Systems

The SCO member states operate under fundamentally different legal systems, from China’s civil law framework to India’s common law traditions. This legal diversity creates significant inconsistencies in interpreting contractual obligations and enforcing arbitral awards across borders. The challenge is compounded by ongoing geopolitical rivalries, such as India-Pakistan tensions over several key matters, which may have complicated consensus-building on major infrastructure initiatives.

Disputes arising from the construction/engineering and energy sectors, which traditionally generate the largest number of ICC cases, together represented just over 45% of all new cases registered.[10] Further, as noted by Global Arbitration Review, State-owned enterprises (SOEs) dominate energy and infrastructure projects under initiatives like China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union. These SOEs often invoke sovereign immunity to evade arbitration processes, complicating enforcement of contracts or awards. For example, if an SOE acts as a state agent (e.g., managing strategic energy assets), its immunity claims could shield assets from enforcement. Foreign investors must secure explicit waivers of immunity in contracts, though effectiveness depends on local laws—Singapore restricts immunity narrowly, while Hong Kong applies it broadly.[11]

A fundamental question frequently arises in both international and domestic commercial arbitration contexts: whether courts should stay or refuse to stay proceedings to minimize multiplicity of proceedings that focus on essentially the same disputes. This issue is particularly relevant for SCO members navigating between arbitral and judicial proceedings for cross-border projects.

The arbitration research notes that it’s normally in parties’ interests to consolidate disputes into one adjudication, with arbitration typically being the preferred mechanism for those bound by arbitration agreements. However, this consolidation becomes problematic when state interests and varying legal traditions intersect, as is common in SCO infrastructure projects.

An example –

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) offers a compelling illustration of the legal challenges arising from the interplay of distinct legal systems within the SCO region. By 2018, Pakistan’s National Judicial Policy Making Committee (NJPMC) had seemingly begun to take actions to limit the judiciary’s power to intervene in CPEC-related projects, to ensure the projects weren’t bogged down by slow resolutions.” This was the result of repeated requests from China aimed at protecting investments, contractors, and financiers involved in CPEC. [12]

This situation underscores the potential for legal friction in major transnational infrastructure projects, as dominant powers seek to modify or influence standard legal procedures to safeguard their investments. As the research notes, transparency and legal transformation pose significant hurdles for CPEC, highlighting the tension between national interests and the need for harmonized legal frameworks to facilitate smooth project implementation.

Harmonized Legal Frameworks

What is to be done is, developing standardized model clauses specifically for energy and infrastructure contracts among SCO member states, which would help reduce ambiguity in jurisdictional claims and enforcement procedures.

Additionally, establishing specialized arbitration panels under the SCO Secretariat would create dedicated forums for resolving energy and infrastructure disputes. These panels could leverage the expertise of the SCO Business Council in mediating complex state-investor disputes while maintaining awareness of the regional geopolitical context.

Environmental and Sustainability Conflicts in Eurasian Development

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) faces significant environmental challenges as its member states pursue rapid infrastructure development, despite stated commitments to environmental protection. Major projects, such as coal-fired power plants in Kazakhstan and large-scale hydroelectric dams in Tajikistan, have raised concerns regarding cross-border environmental impacts and biodiversity loss. While the SCO emphasizes balancing development with environmental protection, as highlighted in the 2023 Summit communique[13] and Kazakhstan’s initiative for the “Year of Environment” in 2024[14], enforcement mechanisms remain underdeveloped. This tension is exemplified by the Russia-Kazakhstan-Uzbekistan “Triple Gas Union,” which, while offering economic benefits by addressing gas shortages, has raised concerns about deepening dependence on fossil fuels and conflicting with SCO members’ goals of transitioning to renewable energy sources.

The integration of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) further complicates environmental governance. These initiatives aim to enhance economic relations, but integrating environmental safeguards remains a critical task. The BRI’s infrastructure corridors intersect with SCO member states, exacerbating ecological pressures. While the SCO has established frameworks like the Concept of Cooperation in Environmental Protection and has engaged in dialogues with UNEP to enhance environmental cooperation[15], these efforts are limited by the lack of binding enforcement mechanisms and reliance on voluntary governance frameworks. As SCO member states navigate the balance between economic development and environmental sustainability, addressing these systemic challenges will be crucial for achieving meaningful progress.

Despite ongoing challenges, integrating green arbitration protocols and institutionalizing the SCO Energy Club as a mediator offers viable pathways for reconciling development with sustainability within the SCO framework. As former secretary-general Vladimir Norov had also been pushing that the SCO member states recognize the importance of environmental protection, environmental safety, and preventing negative consequences of climate change. Initiatives like declaration of 2024 as the “Year of Environment” and the proposal that 2025 be designated as the SCO Year of Sustainable Development (CGTN, 2024) and the SCO-UNEP collaboration on environmental sustainability, there is growing momentum towards addressing the identified shortcomings in environmental governance. By adopting mechanisms for dispute resolution and energy cooperation, the SCO can translate its stated commitments into concrete actions, effectively balancing economic objectives with ecological imperatives.

Solution –

Green Arbitration Protocols

To address the growing number of sustainability-related disputes and concerns, SCO member states should integrate environmental impact assessments (EIAs) into their dispute resolution clauses. This approach would align with the SCO’s 2030 Economic Development Strategy and provide a framework for resolving conflicts between development priorities and environmental commitments.

For instance, future CPEC renegotiations could mandate comprehensive EIAs for new projects, with disputes over environmental compliance directed to specialized arbitration mechanisms. This would ensure that sustainability concerns are given appropriate weight in the dispute resolution process rather than being marginalized as secondary considerations.

Institutionalizing the SCO Energy Club as a Mediator

The transformation of the SCO Energy Club from its current consultative status into a fully institutionalized body represents a significant opportunity for dispute resolution. Originally established in 2013 and currently functioning primarily as a discussion platform, the Energy Club could evolve into a proactive mediator for energy disputes.

The Club could specifically focus on:

- Harmonizing energy strategies between hydrocarbon-producing countries (Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan) and consumer countries (China, India, Pakistan, Turkey, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan)

- Implementing collective energy security measures

- Coordinating investment plans to prevent conflicts

- Developing common economic mechanisms for policy implementation

- Supporting research for cleaner and more cost-effective energy alternatives

The Energy Club is uniquely positioned to resolve disputes over resource allocation, such as the gas swaps between Russia and Central Asian states, and to develop legitimate sanction-navigation strategies that respect international law while protecting member states’ energy security interests.

In conclusion, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is at a critical juncture where its ambition to become a global energy powerhouse is challenged by significant internal hurdles in dispute resolution. The immense judicial backlogs across member states, coupled with legal fragmentation, geopolitical rivalries, and conflicts between development and environmental sustainability, pose a direct threat to the success of unprecedented cross-border collaborations. To move forward, the SCO cannot rely on traditional litigation. The adoption of innovative solutions is imperative, including developing harmonized legal frameworks with specialized arbitration panels, integrating “green arbitration” protocols that mandate environmental impact assessments, and transforming the SCO Energy Club into an institutionalized mediator for energy disputes. By embracing these specialized mechanisms, enhanced by tools like artificial intelligence, the SCO can convert dispute resolution from a potential bottleneck into a catalyst for regional integration, securing its economic objectives and ensuring sustainable development for the entire region.

[1] National Judicial Data Grid, accessed [8th April, 2025], https://scdg.sci.gov.in/scnjdg/?p=home/index&app_token=3ff6301d3eb1aa9899fd11f3115d403ae51c6042baaf6b1c8177fa7ccd407303

[2] National Judicial Data Grid, accessed [8th April, 2025], https://njdg.ecourts.gov.in/hcnjdg_v2/

[3] National Judicial Data Grid, accessed [8th April, 2025], https://njdg.ecourts.gov.in/njdg_v3//?p=home/index&state_code=&dist_code=&app_token=a566bddc8ad53a33f9b3d44ed2288af6bf9eb64a19ac8c6e4acdb0f99f0d300f

[4] Supreme Court Observer. Pendency in the Chandrachud Court: A report card – Supreme Court Observer. Supreme Court Observer. https://www.scobserver.in/journal/pendency-in-the-chandrachud-court-a-report-card/. Published November 21, 2024.

[5] Editor. Over 1.1 million cases pending in Sri Lankan courts, Ministerial Committee informed – Right to Life Human Rights Center. Right to Life Human Rights Center. https://www.right2lifelanka.org/over-1-1-million-cases-pending-in-sri-lankan-courts-ministerial-committee-informed/. Published March 3, 2025.

[6] Law and Justice Commission of Pakistan. (2023). Bi-Annual Report of Judicial Statistics (July–December 2023). Islamabad, Pakistan: Law and Justice Commission of Pakistan.

[7] Judicial reforms of Uzbekistan – a new era, new approaches | Uzbekistan. https://www.un.int/uzbekistan/news/judicial-reforms-uzbekistan-new-era-new-approaches.

[8] Suresh A. The SCO Energy Club as the new energy Agenda setters of Central Asia – Centre for Public Policy Research (CPPR). Centre for Public Policy Research (CPPR). https://www.cppr.in/articles/the-sco-energy-club-as-the-new-energy-agenda-setters-of-central-asia#:~:text=The%20Shanghai%20Cooperation%20Organisation%20(SCO)%20member%20states,50%%20of%20the%20world’s%20known%20uranium%20reserves. Published December 6, 2023.

[9] Yenikeyeff S. Analytics. Valdai Club. https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/the-sco-energy-club-in-the-changing-global-energy-/

[10] International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). ICC Dispute Resolution 2023 Statistics.; 2023. https://iccwbo.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/06/2023-Statistics_ICC_Dispute-Resolution_991.pdf#page=13.

[11] The Asia Pacific Arbitration Review – Global Arbitration Review. https://globalarbitrationreview.com/review/the-asia-pacific-arbitration-review/2021?utm_source=GAR&utm_medium=pdf&utm_campaign=The+Asia-Pacific+Arbitration+Review+2021.

[12] Hongdao, Qian, Sonia Azam, and Hamid Mukhtar. “CHINA PAKISTAN ECONOMIC CORRIDOR: LEGAL INJUNCTIONS AND PROTECTION OF CHINESE INVESTMENT IN PAKISTAN UNDER OBOR INITIATIVE.” European Journal of Research in Social Sciences 6, no. 2 (2018): 29-33.

[13] Joint communique following the 22nd meeting of the Heads of Government (Prime Ministers) Council of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. https://eng.sectsco.org/20231026/Joint-communique-following-the-22nd-meeting-of-the-Heads-of Government-Prime-Ministers-Council-of-963083.html. Published October 26, 2023.

[14] Cgtn. SCO member states reiterate commitment to environmental protection. CGTN. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2024-07-05/SCO-member-states-reiterate-commitment-to-environmental-protection-1uZMRKJxLlC/p.html. Published July 5, 2024.

[15] SCO Secretary-General Zhang Ming takes part in a special SCO-UNEP event and other activities in Nairobi. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. https://eng.sectsco.org/20240305/1287482.html. Published March 5, 2024.